Waiting for Harper

18 Week Ultrasound

For the first time in her pregnancy, Jenna Brown showed up for an appointment alone.

She was almost halfway to term at 18 weeks, and she and Stephen had learned that they were having a girl more than a month earlier. Save your time off for when Harper arrives, Jenna told her husband. It’s just a regular checkup.

As an ultrasound technician slid her scope across Jenna’s belly, Jenna heard the sound of Harper’s heartbeat and stared at the black-and-white screen, anxious to see her growing little girl. But the technician stopped and turned off the machine. “Is someone here with you today?” she asked.

Jenna shook her head. She heard the technician say she’d be right back with Jenna’s doctor but also the unspoken words: Something is wrong.

They had found a tiny black spot, the doctor explained, possibly an opening in Harper’s spine. Jenna would need to see a specialist.

The doctor escorted Jenna to the nurse manager’s waiting area, where Jenna tried to whisper into the phone to Stephen without drawing attention. She watched other women rub their own pregnant bellies, pretending not to listen. But Jenna could see it on their faces – pity for her and gratitude that it wasn’t them.

Stephen rushed from work to meet Jenna at home. The couple filled the next agonizing hour huddled over a computer at their kitchen table, researching. By the time they left to see a specialist at MUSC, they knew that the tiny black spot on the ultrasound could be a much bigger hole, a chasm that separates their daughter from the chance to ever walk, from the ability to control her own bladder and bowels.

When they arrived at MUSC, an ultrasound technician scanned Jenna’s belly once again. This time no one spoke. In that silence, electrified with tension, Jenna felt like she could hear her tears hitting the floor.

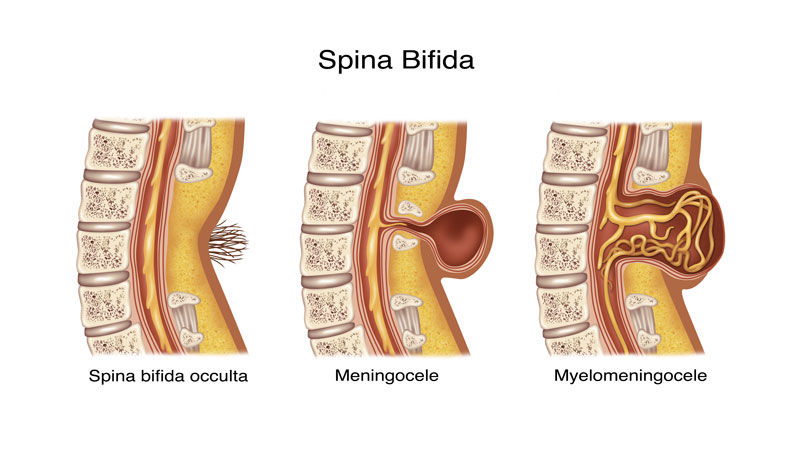

The technician escorted the Browns to a genetic counselor, who confirmed that Harper had myelomeningocele spina bifida, the most severe form of the defect in which a portion of the spinal cord protrudes from the baby’s back. They wouldn’t know the extent of her complications until birth. And even then, they wouldn’t know for sure until she started making -- or missing -- developmental milestones.

For two days, Stephen and Jenna locked themselves in their house, red-eyed and tossing around what-ifs over cold plates of food, unable to eat. They had planned and tried for this baby. And by now, with Jenna’s bump beginning to show more and more each day, they’d made the mental transition into parenthood. They were a family of three, and they wanted to make the best choices for their little girl.

They had two treatment options: Attempt surgery in utero at a specialty hospital in Philadelphia, or wait until Harper’s birth for a spinal repair one day after delivery. Every discussion emphasized the meager time they had to decide. Each conversation woke them from the happy haze of pregnancy and returned them to the daunting reality of Harper’s diagnosis and all its unknowns.

At the end of the two days, they called over their family and told them all at once: They were going to Philadelphia.

They packed everything they needed for Jenna to complete her pregnancy in Pennsylvania. They arranged for Jenna’s parents to watch their dog and alerted neighbors that they might be gone for a while. Family and friends mapped out schedules so that someone always would be in Philadelphia to help. Jenna, a teacher, filed paperwork to take off the rest of the school year. Her colleagues offered to donate their accrued sick leave to cover the unexpected extra time off that otherwise would go unpaid.

Loaded down with luggage, Stephen and Jenna drove through the worst snowstorm to hit the Northeast that year. Then Jenna underwent 12 hours of testing.

At the end of that long day, five doctors crowded into the room with the Browns and delivered their results in medical speak. Physically and emotionally exhausted, Jenna nodded along, until the doctors wrapped up their report and began talking about incontinence and addressing future problems. Jenna looked at her husband, confused. “Are they saying we can’t do this?”

Harper’s spinal cord wasn’t pulling her brain far enough into the spinal column. Her problem, while severe, just wasn’t severe enough to proceed with surgery.

The Browns packed their car. The storm had passed, and bright winter sunshine reflected off the melting snow, as they drove home to Charleston. They called MUSC. They had one option left.

Next >

Medical Glossary

Chiari II malformation: condition associated with MMC spina bifida, in which the brain stem and hindbrain extend beyond the base of the skull into the spinal canal.

ETV (endoscopic third ventriculostomy) surgery: procedure to treat hydrocephalus as an alternative to a shunt. ETV creates an opening in the third ventricle to allow cerebrospinal fluid to flow via an alternative route to be absorbed

Hydrocephalus: enlargement of the normal fluid cavities of the brain, with elevated pressure in the brain cavities.

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): technique that uses magnetic fields to make pictures of internal organs.

Myelomeningocele (MMC): most severe form of spina bifida, in which a portion of the spinal cord, nerves and their coverings protrude through an opening in the back.

Spina bifida occulta: neural tube birth defect, in which structures in the back fail to close properly.

Ventriculomegaly: enlargement of the fluid-filled structures of the brain, called lateral ventricles.

Shunt: device that allows cerebrospinal fluid to drain to another part of the body.

Tethering: condition often associated with spina bifida, in which tissue attachments of the lower spinal cord limit movement of the spinal cord within the spinal column.

Ventricles: each of four communicating cavities within the brain filled with cerebrospinal fluid.

Share Harper's Story

Direct Link

Stay inspired

Find more inspiration from the MUSC Foundation on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, or by signing up for Thank-You Notes - inspirational e-newsletter for monthly stories about how everyday heroes are changing what’s possible.

Change what's possible

Although a state institution, MUSC only receives 5 percent of its budget from state funding. As such, we depend on private gifts from everyday heroes in our community in order to fulfill our mission of groundbreaking research, compassionate patient care and world-class education. In short, you can make stories like Harper’s possible.

I want to change what's possible

Make a gift