Harper’s Birth

A paper bird decorated the door of hospital room 592 -- not an origami crane, but a stork.

Inside, Donna Pender rubbed her daughter’s belly one last time and told Jenna, sleepless and makeup-free, that she looked beautiful. “I’m so proud of you,” Donna said. “And I love you.”

Stephen’s mom stopped by and asked to pray. Stephen, Jenna, Jenna’s parents and Stephen’s mom clasped hands around Jenna’s hospital bed and asked God to watch over Harper’s delivery. And as doctors cleared everyone out to take Jenna for her spinal block, Stephen’s father gave Jenna a hug and a wink. “Scream loud,” he said, “so we can hear you.”

Jenna and Stephen had woken up at 4:30 a.m. on June 17, 2015. Or rather, they had gotten out of bed at 4:30 a.m., finally allowing their bodies to catch up to their minds that had been pacing the room since they lay down the night before.

Jenna took a shower, rinsing her skin with an antiseptic solution to prepare for surgery, paying close attention to her abdomen, as the nurse had instructed. She and Stephen arrived at MUSC before sunrise, and Jenna turned off her phone to insulate herself from the barrage of calls, texts and social media notifications that accompany a scheduled C-section.

Anyone she might need to reach was at the hospital anyway, wearing Hope for Harper T-shirts with yellow ribbons for spina bifida awareness.

The operating room moved like a ballet, with each person performing a specific role to complete the surgery with elegance and efficiency. Someone handed Stephen a gown, while another technician scooped Jenna’s ponytail into a hairnet. Like backstage during a scene change, everyone pulled on matching pale blue gowns. Someone called out each instrument by name.

From the first moment of incision until Harper’s birth took six minutes. Months of wait and worry and hours of meticulous preparation that morning all came down to this – a process that took no longer than brewing a pot of coffee. Against the steady beep of monitors and IV drips, an army of gloved fingers snipped and pried and pulled on Jenna’s abdomen, until a pair of hands lifted Harper screaming into the room, and someone shouted, “Happy birthday!”

Jenna heard a voice say, “She’s so cute!” but nothing else, as nurses whisked her daughter away to be examined. While the surgeon worked on Jenna’s stitches, Stephen followed Harper, listening to the commentary that trailed her bassinet rolling down the hall.

“6 pounds, 15 ounces, and 20 inches.”

“Her head doesn’t really look that big.”

And the facts that would define the rest of Harper, Jenna and Stephen’s life:

“She’s moving her legs great.”

“The defect looks like it’s covered with skin, so that’s good.”

“She has great grasp in both toes, Dad.”

A nurse took Harper’s footprints upside down, since Harper couldn’t lie on her back, and Stephen returned to his wife. He struggled to fashion the words to tell Jenna what he’d learned, while she searched his face to understand his tears.

It’s covered with skin, he finally told her. She can move her legs.

A nurse wheeled in the bassinet, lifted the crying baby and placed her on Jenna’s chest. In another strange, bright room, Harper quieted when she heard the sound of the heartbeat she’d known so long. The nurse draped a warm white and blue-striped blanket over them, and Jenna studied her daughter.

“There you go,” Jenna told Harper. “You’re OK, sweet girl.”

Harper wanted to nurse, but with surgery the next morning, she had to wait to eat. Barred from fulfilling a natural maternal instinct, Jenna wiped away her own tears when Harper whimpered. The nurse leaned over and touched Jenna’s shoulder. “She’s going to be fine,” the nurse promised and then reminded Jenna, gently, that Harper had to move up to the neonatal intensive care unit now.

The nurse rolled Harper out to the hallway crowded with family and close friends clutching coffee cups and waiting for this moment. They peered into the bassinet, smiling and cooing and snapping photos on their phones. Stephen, following behind, paused to talk with his mother-in-law – about the birth, Harper’s lesion, their next steps. But as he opened his mouth to speak, after five months of uncertainty, he leaned in to her shoulder and cried.

He went back to get Jenna and pushed her up to the neonatal intensive care unit in a wheelchair. They brought a pink and gray headband that they’d packed and slipped it onto Harper’s head.

Dr. Eskandari walked in and smiled. His wife insists on putting the same hair accessories on their daughter, too, he told them.

Watching the new baby, he said, “Hey, look at those feet going!”

He still couldn’t give Jenna and Stephen answers about Harper’s bowel and bladder function, but the layer of skin over her lesion had protected her from paralysis. He explained to the Browns that hydrocephalus, or fluid buildup on Harper’s brain, would spike after surgery. He would monitor her head growth to see if Harper needed a shunt.

Jenna and Stephen listened and nodded, as he outlined the nearly five-hour surgery awaiting their daughter in the morning, alternating glances between their new baby and the man who would hold her future – and theirs – in his hands.

“You’re so beautiful,” Jenna whispered to Harper, stroking her arm. “You’re perfect.”

Next >

Medical Glossary

Chiari II malformation: condition associated with MMC spina bifida, in which the brain stem and hindbrain extend beyond the base of the skull into the spinal canal.

ETV (endoscopic third ventriculostomy) surgery: procedure to treat hydrocephalus as an alternative to a shunt. ETV creates an opening in the third ventricle to allow cerebrospinal fluid to flow via an alternative route to be absorbed

Hydrocephalus: enlargement of the normal fluid cavities of the brain, with elevated pressure in the brain cavities.

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): technique that uses magnetic fields to make pictures of internal organs.

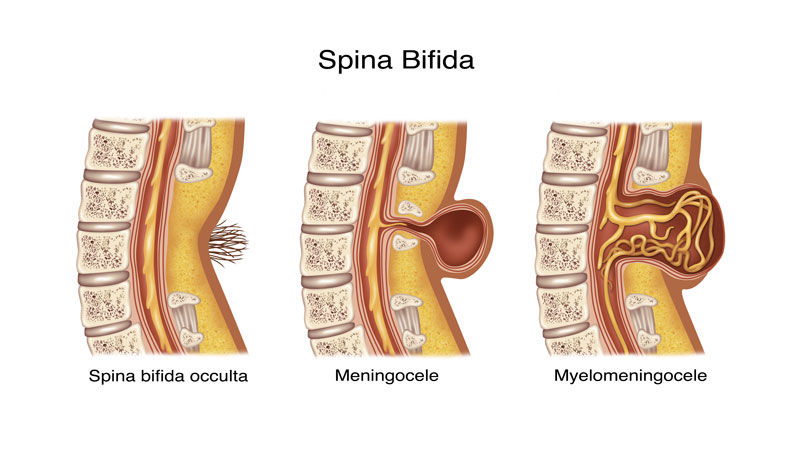

Myelomeningocele (MMC): most severe form of spina bifida, in which a portion of the spinal cord, nerves and their coverings protrude through an opening in the back.

Spina bifida occulta: neural tube birth defect, in which structures in the back fail to close properly.

Ventriculomegaly: enlargement of the fluid-filled structures of the brain, called lateral ventricles.

Shunt: device that allows cerebrospinal fluid to drain to another part of the body.

Tethering: condition often associated with spina bifida, in which tissue attachments of the lower spinal cord limit movement of the spinal cord within the spinal column.

Ventricles: each of four communicating cavities within the brain filled with cerebrospinal fluid.

Share Harper's Story

Direct Link

Stay inspired

Find more inspiration from the MUSC Foundation on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, or by signing up for Thank-You Notes - inspirational e-newsletter for monthly stories about how everyday heroes are changing what’s possible.

Change what's possible

Although a state institution, MUSC only receives 5 percent of its budget from state funding. As such, we depend on private gifts from everyday heroes in our community in order to fulfill our mission of groundbreaking research, compassionate patient care and world-class education. In short, you can make stories like Harper’s possible.

I want to change what's possible

Make a gift