Repairing Harper’s Spine

Stephen asked the question: “When are they coming to get her?”

He and Jenna held Harper in the dim blue light of the neonatal intensive care unit. Hums and beeps charted vital signs of the hospital’s tiniest patients and counted out loud the Browns’ every second together.

Some parents crowd around plastic bassinets in this unit for months, marking each day – sometimes every hour -- as a victory for their babies born too soon or too weak. But Harper was just passing through.

Swaddled in a pink-striped blanket embroidered with a yellow spina bifida awareness ribbon, she wore a flapper-style headband with a pale pink blossom. A nurse answered Stephen’s questions without words, as she lifted Harper from his chest and placed her into a bassinet for transport to the operating room.

Jenna and Stephen said nothing. Jenna gripped the edge of the plastic box that held her daughter and reached in to stroke Harper’s head, while Stephen rubbed his wife’s shoulders – both of them unsure what to do with their empty hands that moments before had held their little girl.

After months of waiting, Harper was here. That black dot on an ultrasound – an anatomical question mark – now had an answer. But the relief lasted only a day. With the first sunrise since Harper’s birth came a new anticipation.

The nurse slipped a black mask over Harper’s eyes to protect them from the harsh white operating room lights and rolled her out. Stephen pushed Jenna out of the neonatal intensive unit in a wheelchair, and Dr. Eskandari met them in the hallway. He knelt beside Jenna.

“It’s going to be fine,” he told her. “We’re going to take care of her.”

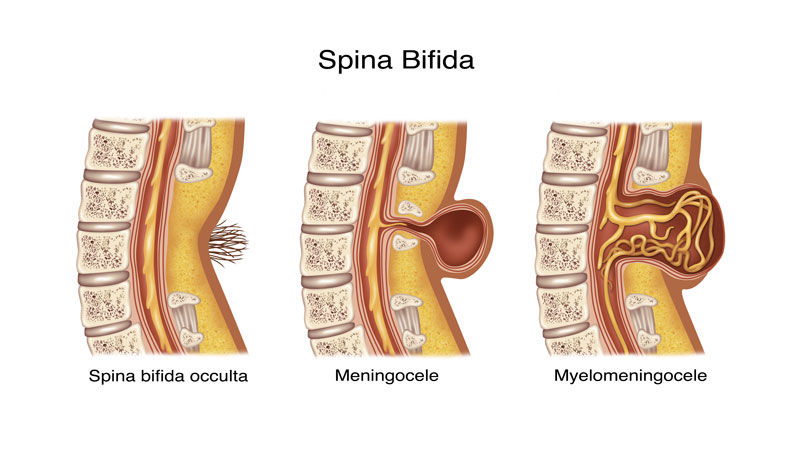

Harper’s diagnosis, myelomeningocele spina bifida, means her spinal cord had herniated from her back without the protective layers of membrane, bone and muscle that normally insulate a person’s bundle of nervous tissue from the world.

Surgery doesn’t repair nerves or improve a patient’s ability to move. Rather, it prevents infection. And the procedure should take place within three days of birth – the sooner, the better.

Dr. Eskandari trained under four pediatric neurosurgeons while in residency at the University of Utah, three during a fellowship at Stanford and two more working in Uganda before his seventh and final year as a resident. There, poor nutrition in mothers translates to more babies with neural tube defects. Dr. Eskandari saw 11 myelomeningocele spina bifida cases in the two months he spent in Uganda, the same number he treats annually at MUSC.

He trained in settings that varied from a world-class teaching hospital with Ivy League pedigree to a medical facility in East Africa, where the power went out as often as 25 times each day, interrupting procedures until someone could rouse the single maintenance man who held a key to the generator tucked into a shed outside. On nights or overcast days, staff members would hold flashlights and cell phones over patients while waiting for the generator so that Dr. Eskandari could continue his procedures.

For seven years he observed and asked questions. He practiced every aspect of surgery hundreds of times alongside mentors, mentally filing away techniques he liked and some he didn’t. One neurosurgeon taught him always to review the case before beginning – to perform the surgery in his mind before ever touching an instrument to bare skin.

Dr. Eskandari likes to wash his patients himself, a task often left to support staff. He uses that time to position the patient, to review the exact location of the surgery and to ensure that everything is as sterile as possible to prevent infection later.

He plays reggae in his operating room. Its characteristic rhythm, with guitar chops on the offbeat, keeps his mind moving through the paces and neither stresses nor lulls him. He figures none of his patients would object; after all, he doesn’t know anyone who doesn’t like reggae.

When he arrived in the operating room on June 18, two 3-inch pink feet poked out from under white surgical linens. Dr. Eskandari began Harper’s case by scrubbing her back with an alcohol-based antiseptic.

Then he drew an ellipse on her back, a thin curve of black marker to indicate where the healthy skin stopped and where he would close her incision after repairing the defect. After that, he washed her again, this time with iodine that left a brown-red stain on her skin.

He walked out to continue his mental preparation over a deep metal sink, where he washed each finger on both sides and both arms up past his elbows – a thorough, practiced routine -- while his team draped Harper under pale blue cloth, refining the workspace to a single rectangle of one-day-old skin.

A spinal cord begins as a flat plate and rolls into a tube during fetal development. But in spina bifida cases, the cord stays flat. Dr. Eskandari would pull unhealthy tissue away from the raw spinal cord and fold the cord into the proper tube shape. He then would restore the layers of dura, muscle, fat and skin that protect a spinal cord and prevent fluid from leaking out.

When he finished scrubbing in, Dr. Eskandari pressed his hands together at his fingertips to avoid touching anything and opened the door to the operating room with his back.

Bob Marley’s “No Woman, No Cry” played, as he made the first incision.

One floor up, 15 relatives and close friends crowded into Jenna’s postpartum hospital room. Unsure of what to say, they looked at Stephen and Jenna. Their silent pity made the walls feel tighter, the air almost too heavy to breathe.

The men left to get lunch and to give Jenna some privacy to try to pump milk for Harper. When a nurse suggested that the women do the same, no one budged.

Jenna produced a few meager drops. Her sister, Lauren, saw the overwhelming frustration on Jenna’s face and asked her to take a walk. As they stepped away from the confines of the room and into the natural light of the hallway, Jenna felt her shoulders relax beneath her hospital gown. Lauren cracked a joke about everyone crammed into the room, and Jenna laughed for the first time.

When Lauren spotted Stephen returning from lunch, she excused herself. Jenna and Stephen decided to stay in the hallway, just the two of them, until Dr. Eskandari returned. The couple waited in silence, their eyes trained on the swinging doors to the children’s hospital.

In the operating room just beyond those doors and down the hall, Dr. Eskandari understood why doctors in Philadelphia had disqualified Harper for in utero surgery. Only the tip of her spinal cord had adhered to the abnormal tissue, so the cord didn’t pull her brain down as significantly as expected.

Harper’s case, while still the most severe form of spina bifida, was one of the mildest examples Dr. Eskdandari had seen. He spent an hour and a half removing skin, repairing her spinal cord and then closing her incision with stitches as fine as hair.

He stepped through the doors leaving the children’s hospital and stopped when he found Jenna and Stephen leaning against the wall, waiting for him. Still wearing his surgical cap, he hugged Jenna and smiled.

“It went well,” he said. “It went really well.”

Next >

Medical Glossary

Chiari II malformation: condition associated with MMC spina bifida, in which the brain stem and hindbrain extend beyond the base of the skull into the spinal canal.

ETV (endoscopic third ventriculostomy) surgery: procedure to treat hydrocephalus as an alternative to a shunt. ETV creates an opening in the third ventricle to allow cerebrospinal fluid to flow via an alternative route to be absorbed

Hydrocephalus: enlargement of the normal fluid cavities of the brain, with elevated pressure in the brain cavities.

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): technique that uses magnetic fields to make pictures of internal organs.

Myelomeningocele (MMC): most severe form of spina bifida, in which a portion of the spinal cord, nerves and their coverings protrude through an opening in the back.

Spina bifida occulta: neural tube birth defect, in which structures in the back fail to close properly.

Ventriculomegaly: enlargement of the fluid-filled structures of the brain, called lateral ventricles.

Shunt: device that allows cerebrospinal fluid to drain to another part of the body.

Tethering: condition often associated with spina bifida, in which tissue attachments of the lower spinal cord limit movement of the spinal cord within the spinal column.

Ventricles: each of four communicating cavities within the brain filled with cerebrospinal fluid.

Share Harper's Story

Direct Link

Stay inspired

Find more inspiration from the MUSC Foundation on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, or by signing up for Thank-You Notes - inspirational e-newsletter for monthly stories about how everyday heroes are changing what’s possible.

Change what's possible

Although a state institution, MUSC only receives 5 percent of its budget from state funding. As such, we depend on private gifts from everyday heroes in our community in order to fulfill our mission of groundbreaking research, compassionate patient care and world-class education. In short, you can make stories like Harper’s possible.

I want to change what's possible

Make a gift