Best- and Worst-Case Scenarios

Another windowless room with neutral walls and a sheet of stiff white paper stretched across an exam table -- an invitation for poking and prodding and personal conversations.

Jenna and Stephen Brown had been here, or somewhere just like it, too many times in a few short weeks. From their baby’s devastating spina bifida diagnosis in Charleston, to hopeful testing at a hospital in Philadelphia and then the crushing news that they didn’t qualify for surgery. In these colorless, sterile rooms, they had experienced an emotional spectrum.

Now here they were, back home in Charleston, once again at MUSC in yet another exam room – this time to see a pediatric neurosurgeon and talk about operating after Harper’s birth. Exhausted from weeks of frenzied research that ended in disappointment, they showed up without expectations about Dr. Ramin Eskandari.

He was only a few years older than Jenna and Stephen and a new father himself. He took the time to listen to them, to hear their story. He talked about other surgeries, potential outcomes.

Stephen pressed him for numbers. What are the odds that Harper would need a shunt to route excess fluid away from her brain? What’s the chance that she would need multiple surgeries? How likely would she be able to walk or control her own bodily functions?

Dr. Eskandari made no promises. He works in tangibles -- in nerves and skin, in shiny sterile instruments and surgical lighting. Until Harper arrived, he couldn’t speak beyond possibilities.

But he also understands the distinct torture of uncertainty. Dr. Eskandari’s early childhood took shape against a backdrop of worry during the Islamic Revolution in Iran, where his parents found themselves in danger for dissenting from the rising party. They fled with Ramin and his sister, traveling across the countryside to family members’ homes and leaving everything behind.

Dr. Eskandari doesn’t remember the noise of protest or gunfire, the way you feel those sounds inside your body like a second, irregular heartbeat, when they aren’t in a movie or a newspaper but rather on the other side of your own walls. And he doesn’t remember wondering every time his mother and father left whether they would make it home.

When he thinks about Iran, he instead remembers the feeling of water drops in his hair, the smell of mud underfoot and the unburdened happiness of riding on the handlebars of his best friend’s bicycle in the rain. A practical clinician, he suspects that he suppressed the rest.

Today he stands out not only for his remarkable abilities but for his genuine compassion. If there’s such a thing as a surgeon’s surgeon – a crotchety doctor who manages patients with the same finesse that a short-order cook handles a tomato – then Dr. Eskandari is the opposite. He’s the patient’s surgeon who lays a friendly hand on the shoulder of an upset parent, pauses often during tough conversations to assess and never leaves without answering every question.

He decided on this profession soon after his family made it out of the Middle East. His parents landed in Belgium as a stopover on their journey to join family in Michigan. While the Eskandaris waited for green cards, his mother took her children to the park each day.

During the week, the park filled with retirees also passing the time. When young Ramin told his mother how ugly the older people were, she reminded him that she would grow old too. But you can become a plastic surgeon, she challenged, and keep me beautiful.

Ramin failed to see the jest in her suggestion. He refused to consider his mother – with her long, dark hair and smooth skin – as one of the people he saw sitting on park benches. For years, whenever anyone asked him what he wanted to do as an adult, he said he would become a plastic surgeon.

His motivation changed as he matured and, rather than preserving his mother’s beauty, he wanted to help disfigured children. He credits his interest in pediatric neurosurgery to a seventh grade science teacher in Michigan. The teacher once had animal brains on hand – Dr. Eskandari suspects she worked out a deal with the taxidermy instructor down the hall -- for her students to dissect.

Dr. Eskandari, straight-faced, calls that the best day of his life – but it also posed a problem. After class, he told the teacher that the lesson amazed him but didn’t quite fit with his plans to help children. You can work on brains, his teacher told him, in a field called neurosurgery – and you can specialize in pediatric neurosurgery to work with kids.

That was the day 12-year-old Ramin Eskandari began telling people that he would become a pediatric neurosurgeon.

He completed medical school at Wayne State in Detroit and residency at the University of Utah. He landed at MUSC in 2014, following a fellowship at Stanford. When Dr. Sunil Patel, chairman of MUSC’s Department of Neurosurgery, talks about Dr. Eskandari, he speaks of MUSC’s good fortune. Prestigious children’s hospitals across the country had courted Dr. Eskandari, but he chose MUSC as a place where he could provide world-class care and conduct groundbreaking research at the same time.

Jenna and Stephen heard Dr. Eskandari’s unsolicited approval from everyone they met. Nurses, doctors and counselors who spotted his name on their chart looked up at the Browns with a congratulatory expression, as they volunteered some praise.

So now, in one more exam room meeting with Dr. Eskandari – their only remaining option -- Jenna and Stephen had to choose to believe that this time was different.

Next >

Medical Glossary

Chiari II malformation: condition associated with MMC spina bifida, in which the brain stem and hindbrain extend beyond the base of the skull into the spinal canal.

ETV (endoscopic third ventriculostomy) surgery: procedure to treat hydrocephalus as an alternative to a shunt. ETV creates an opening in the third ventricle to allow cerebrospinal fluid to flow via an alternative route to be absorbed

Hydrocephalus: enlargement of the normal fluid cavities of the brain, with elevated pressure in the brain cavities.

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): technique that uses magnetic fields to make pictures of internal organs.

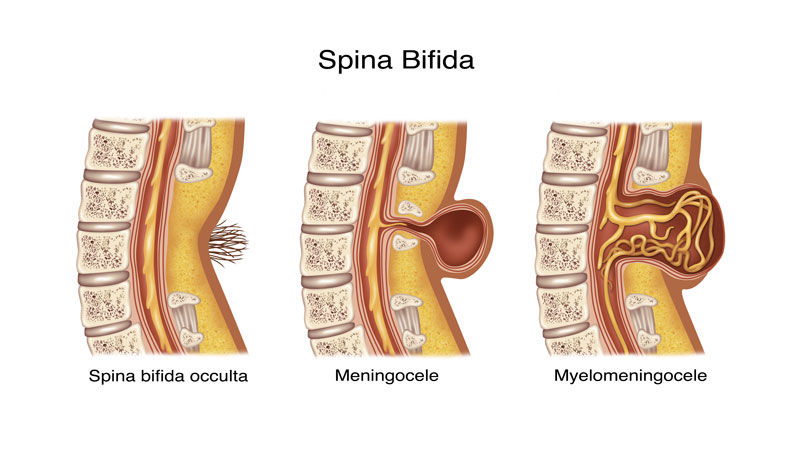

Myelomeningocele (MMC): most severe form of spina bifida, in which a portion of the spinal cord, nerves and their coverings protrude through an opening in the back.

Spina bifida occulta: neural tube birth defect, in which structures in the back fail to close properly.

Ventriculomegaly: enlargement of the fluid-filled structures of the brain, called lateral ventricles.

Shunt: device that allows cerebrospinal fluid to drain to another part of the body.

Tethering: condition often associated with spina bifida, in which tissue attachments of the lower spinal cord limit movement of the spinal cord within the spinal column.

Ventricles: each of four communicating cavities within the brain filled with cerebrospinal fluid.

Share Harper's Story

Direct Link

Stay inspired

Find more inspiration from the MUSC Foundation on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, or by signing up for Thank-You Notes - inspirational e-newsletter for monthly stories about how everyday heroes are changing what’s possible.

Change what's possible

Although a state institution, MUSC only receives 5 percent of its budget from state funding. As such, we depend on private gifts from everyday heroes in our community in order to fulfill our mission of groundbreaking research, compassionate patient care and world-class education. In short, you can make stories like Harper’s possible.

I want to change what's possible

Make a gift