'Miracle Baby'

During her first feeding, Harper hungrily swallowed too much milk too fast. Jenna and Stephen watched, horrified, as their daughter -- who made it through a high-risk birth and delicate surgery on her spine the next day -- turned blue.

A nurse whisked Harper away and left her parents cradling doubt. Were they ready for challenges at home, when no one could swoop in?

Jenna took a CPR class in Harper’s room and watched everything the nurses did. She and Stephen wanted to change diapers, provide bottles and meet Harper’s every need as if they were on their own.

The Browns planned for Harper’s hospital stay to last a month. Her care team at MUSC told them to prepare for weeks of sleeping on couches and commuting to and from the hospital, but Harper recovered and thrived faster than anyone anticipated.

When a nurse came in on Harper’s due date – a week after her birth – she carried discharge papers. Jenna called Stephen at work. “It’s time to come take your wife and baby girl home,” she said. But she worried.

Jenna dressed Harper in a white ruffled dress, and she and Stephen loaded her into a brand-new car seat in the back of their white Infiniti sedan. Doctors gave Harper clearance to ride home but otherwise wanted no pressure on her back.

Stephen drove slowly, carefully. Every wheel turn seemed suspended in time, and the 15-mile trip home to Hanahan felt like another unnerving test of patience for the new parents. Harper slept the entire way, and Jenna watched her tiny chest rise and fall from the seat beside her.

Three weeks later, Jenna’s friend – a labor and delivery nurse – stopped by to meet Harper. The friend noticed that Harper struggled to breathe at times.

Jenna and Stephen brought her to see their pediatrician a day before their scheduled one-month appointment. The doctor watched Harper’s breathing – nothing to worry about, he said – and completed her scheduled checkup while they were there.

He discovered that Harper’s head circumference had spiked 2 centimeters since birth. Dr. Eskandari was in Atlanta with his wife and baby daughter, so the pediatrician referred Harper to the MUSC Children’s Hospital emergency room.

An imaging scan confirmed the Browns’ fears: The ventricles in Harper’s brain had grown.

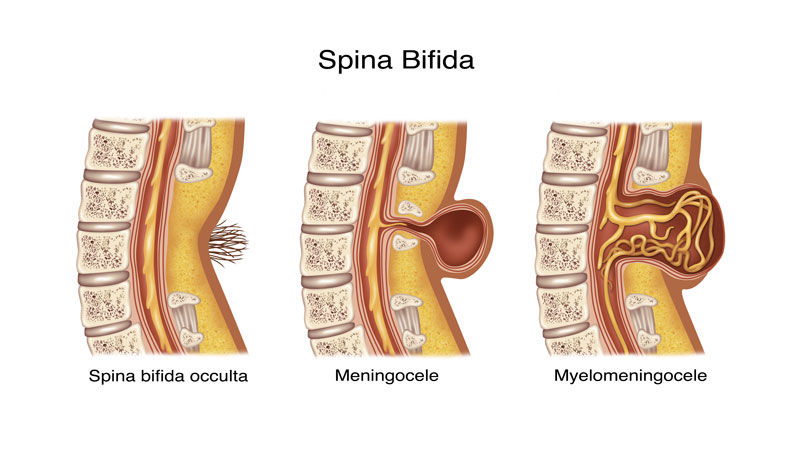

Spina bifida patients often develop hydrocephalus, or fluid buildup on the brain. A Chiari II malformation, part of Harper’s diagnosis, pulls the cerebellum and brain stem down and can obstruct fluid flow, causing rapid head growth.

Jenna and Stephen drove home expecting to schedule a surgery to install a shunt that would divert fluid from Harper’s brain. But the next morning Dr. Eskandari called from his cell phone. He’d had the images sent over to him on his trip, and he told them not to worry just yet. So far, Harper still fell within the target numbers in his mind.

The Browns bought a flexible measuring tape to check Harper’s head at home and track her growth between appointments, even though Dr. Eskandari warned that they’d only drive themselves crazy. But after so many months of unknowns, they needed that scrap of control.

They always knew the possibility that Harper would need a shunt, along with all the other possibilities that now seemed so much worse. Harper might not have been able to move her feet. In fact, she could have been paralyzed from her inner thigh down. And yet their baby girl seemed to elude each frightening possibility that emerged.

A few days before Harper turned 2 months old, Jenna tickled the spot on Harper’s thigh where her paralysis would have begun. Harper giggled for the first time.

Jenna returned to work when Harper turned three months old, leaving her mother and sister-in-law with detailed notes on the baby’s routine and warning signs of trouble. Jenna maintained her composure for her students but ticked off the minutes between each break from class when she could check her phone for photos and updates. She filed for family medical leave every Friday to attend appointments with an early interventionist who monitored Harper’s progress toward developmental milestones.

Harper met them all – lifting her head, kicking her legs, rolling over. She started eating solid food at four months old, devouring peas, carrots and squash.

When the Browns returned to see Dr. Eskandari in December, just before Harper turned 6 months old, he marveled at Harper. Her blue eyes sparkled beneath a white and gold polka dot bow, and she smiled at her neurosurgeon.

Not only had she hit every developmental milestone -- as if her diagnosis a year earlier never had happened -- but her skull growth remained within his safe parameters. Dr. Eskandari told Jenna and Stephen that they could wait until she turns 1 for her next brain scan.

He reminded the Browns of the rarity of their daughter’s outcome. As he sat on the other side of the exam room, listening, Stephen wiped tears from his face. One year earlier he had stared at a black dot on an ultrasound screen, a hole filled with questions. And now – finally — were the answers he’d spent every day hoping to hear.

“You’ve got yourself a little—” Dr. Eskandari began.

Jenna answered for him. “Miracle.”

Dr. Eskandari nodded. “Miracle kid.”

Epilogue

Harper Lane Brown took her first solo steps on Aug. 15, 2016.

She is now 2 years old and runs, dances and swims. She loves Mickey Mouse and shooting hoops. She speaks in complex sentences and knows how to spell her name. Harper never required additional surgery.

Jenna and Stephen Brown, along with Harper, now represent MUSC as the campaign family for the Pediatric Neuroscience Research Fund. Jenna remained a middle-school teacher for a year and a half after Harper’s birth before becoming a full-time volunteer, advocate and spokeswoman for pediatric neuroscience awareness and children’s health in general.

Dr. Ramin Eskandari sees an estimated 1,000 patients per year at the MUSC Children’s Hospital and performs about 200 surgeries annually. Some of his most notable recent cases include replicating a pediatric brain tumor cell line that now can be used in research internationally, and successfully treating a baby whose skull fused prematurely due to a disfiguring birth defect.

Dr. Eskandari’s daughter, Kiara, is Harper’s age. Kiara and Harper have become close friends, just like their parents.

What's Next

Learn more about where this story came from, visit the gallery for more precious moments with the Brown family or join usby subscribing to our newsletter, following us on social media, or making a gift to the MUSC Together fund.

Medical Glossary

Chiari II malformation: condition associated with MMC spina bifida, in which the brain stem and hindbrain extend beyond the base of the skull into the spinal canal.

ETV (endoscopic third ventriculostomy) surgery: procedure to treat hydrocephalus as an alternative to a shunt. ETV creates an opening in the third ventricle to allow cerebrospinal fluid to flow via an alternative route to be absorbed

Hydrocephalus: enlargement of the normal fluid cavities of the brain, with elevated pressure in the brain cavities.

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): technique that uses magnetic fields to make pictures of internal organs.

Myelomeningocele (MMC): most severe form of spina bifida, in which a portion of the spinal cord, nerves and their coverings protrude through an opening in the back.

Spina bifida occulta: neural tube birth defect, in which structures in the back fail to close properly.

Ventriculomegaly: enlargement of the fluid-filled structures of the brain, called lateral ventricles.

Shunt: device that allows cerebrospinal fluid to drain to another part of the body.

Tethering: condition often associated with spina bifida, in which tissue attachments of the lower spinal cord limit movement of the spinal cord within the spinal column.

Ventricles: each of four communicating cavities within the brain filled with cerebrospinal fluid.

Share Harper's Story

Direct Link

Stay inspired

Find more inspiration from the MUSC Foundation on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, or by signing up for Thank-You Notes - inspirational e-newsletter for monthly stories about how everyday heroes are changing what’s possible.

Change what's possible

Although a state institution, MUSC only receives 5 percent of its budget from state funding. As such, we depend on private gifts from everyday heroes in our community in order to fulfill our mission of groundbreaking research, compassionate patient care and world-class education. In short, you can make stories like Harper’s possible.

I want to change what's possible

Make a gift